Disney Anniversary

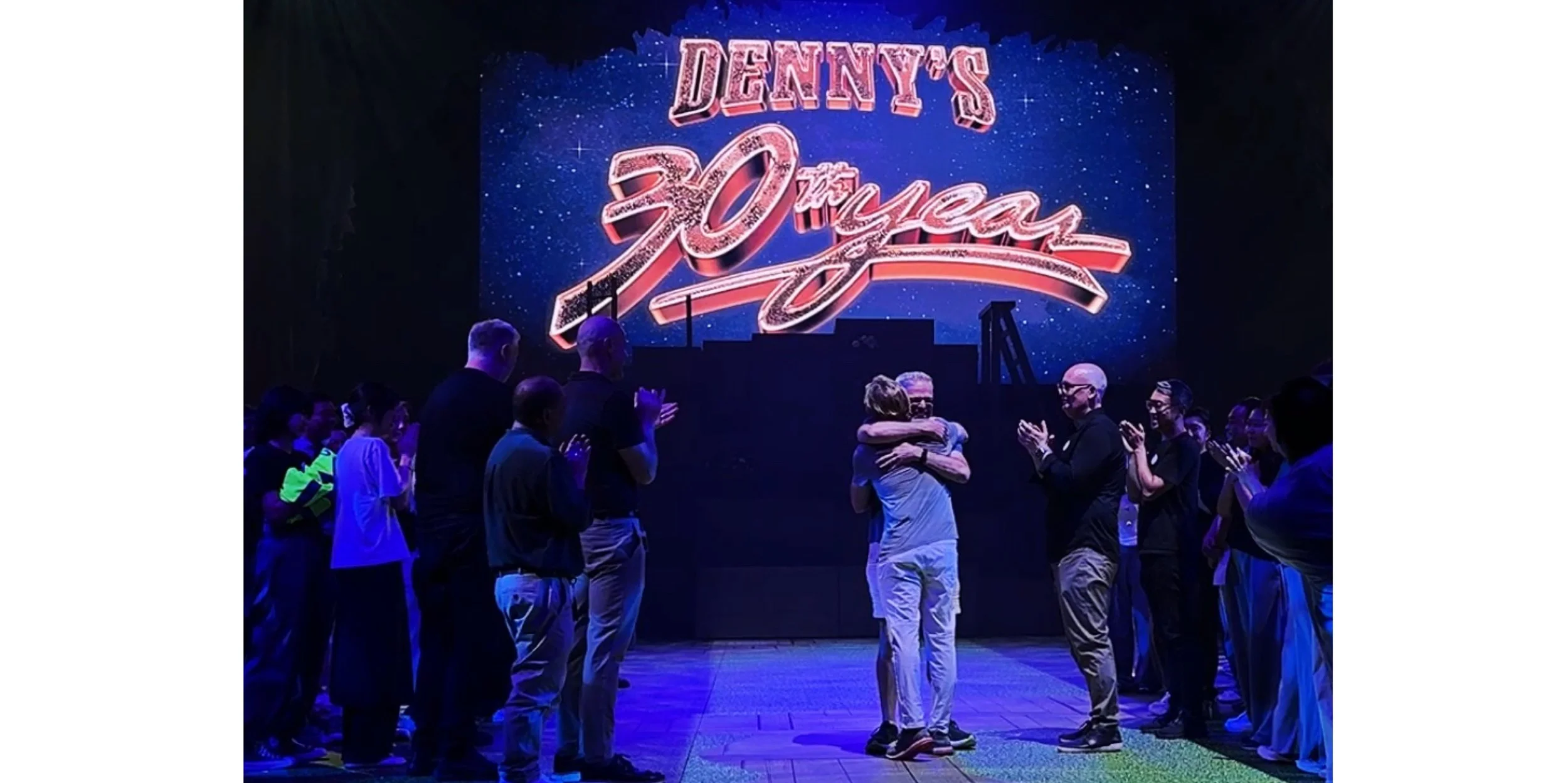

This was the moment I joined the surprise celebration to mark Denny’s 30th official year working at Disney. 😮

Very grateful to his amazing team for conspiring to bring me backstage. And very proud of Denny for reaching such an incredible milestone. 🥰

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

Barcelona and Location Independence

The biggest change I’ve noticed in Barcelona since I was last here seven years ago is the way its popularity has soared. I don’t mean as a travel destination, we all know about the city’s efforts to clamp down on over-tourism. I mean as a place for people to base themselves for work, especially now that location-independent careers have become more accepted since COVID-19. It’s an incredibly well-connected city, offering a balanced lifestyle, in a permissive culture-rich environment.

On the subject of location-independence, I need to forgo my usual British fake modesty for a second… because we were so far ahead of the curve on this when I co-founded ChapmanCG in 2008. Peripatetic and paperless, we were liable to pop up anywhere in the world, it’s no wonder that I still live these values six years into my retirement from the company. And if that means that for a short while I get to see the people in these photos - including Ben Davies, who we hired into the company 15 years ago - then I don’t yet see a reason to stop.

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Mala and Me

These days it’s not so common for a Global Head of HR to still make time to see me when they pass through Shanghai. So when it happens, I feel the need to celebrate it, especially when they happen to be the fabulous Mala Singh.

We covered a hundred topics over breakfast, and exchanged survival tips on managing the everyday complexities of this multifarious multi-polar world. The only teeny tiny difference between us being that she also manages the worldwide people strategy for Electronic Arts (EA) and the co-parenting of 3 kids, whereas I can barely manage myself.

Thank you so much Mala. And let this also be a guilt-trip to all the other CHROs reading this right now. Do not come through Shanghai without becoming breakfast buddies. ☕️

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Fifteen Years of Nurture

For the last 15 years, I have nurtured a network of HR and Talent leaders around the world, but especially in Tokyo. My ethos was always simply to treat everyone as human beings, rather than to commoditise relationships by treating them as “clients” or “candidates.”

I’m not sure I was always successful in this endeavour. But now that I’ve retired as a headhunter, I’m happy that I can still count so many of them as friends. And I’m grateful that a handful of these special people were able to make some time for a meet-up in this special city.

過去15 年間、私は世界中、特に東京において人事および人材リーダーのネットワークを築いて来ました。私の理念は常に、すべての人を「顧客」や「候補者」として扱うことで関係性を商品化せず、人として関わることでした。

この取り組みで常に成功したかどうかはわかりません。しかし、ヘッドハンターとして引退した今でも、たくさんの人をまだ友人と呼べることに満足しています。そして、少数の特別な人たちと時間を共有し、この特別な都市で集まれたことに感謝しています。

これからもよろしきお願いします❣️

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Interview with the China-Britain Business Council

These days I have a love/hate relationship with the label ‘entrepreneur’. But the life of an independent content creator and an entrepreneur is very similar. You can be fueled with pride for your mission one day, and paralysed with doubt and self-loathing the next. But with the help of positive people around you, you do have the chance to live comfortably with this creative tension, and preserve your equilibrium.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the China-Britain Business Council Website version, see here.

Just Shut Up And Listen

In my decade as a headhunter and year as a podcaster, I estimate that I have had meetings with around 10,000 people. And if I had to hone down my 3 top tips for getting the most out of interviews, they would be simple:

Just shut up and let your guest speak;

Mirror the energy of your guest, don’t allow it to be the other way around; and

Listen deeply.

If you could condense your interview technique into just 3 top tips, what would they be?

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Career & Coffee

The two simplest pieces of advice I can give to anyone who feels stuck in their career today is:

Find a good career advisor you can trust. Not just someone who tells you what you want to hear. Not just someone who tells you about jobs in the market. But someone who truly listens.

Listen to the Career & Coffee Podcast. 16 episodes released over 8 weeks, specifically targeting people who are feeling stuck.

I don’t think I gave much practical advice in my episode, but I’m sure the other 15 will be amazing. Thank you for the fun interview, Ann Calman and Amelia Novakovic.

Today I Bid a Final Farewell to ChapmanCG

It has been just over a decade since we started The Chapman Consulting Group in Singapore. It is now the largest organisation of its kind in the world, with senior HR appointments in 69 countries, and over 110,000 executive HR leaders in its global network. Playing a part in this trajectory has been by far the most rewarding professional achievement of my life, and I owe a huge debt of thanks to Matt, to past and present members of the amazing ChapmanCG team, and to the tens of thousands of HR professionals around the world whom I’ve learnt from, and hopefully helped in some small way in return.

With a new strategic investment from Will Group (株式会社ウィルグループ), and the continuity of it’s existing management team, I have no doubt that ChapmanCG will maintain its position in offering the world’s best Executive Search solution for the HR Profession. I will no longer be part of the ChapmanCG story moving forward. But I wish everyone all the best, and look forward to our paths crossing again in a personal capacity.

Oscar

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Job-Seekers In Your 50s: What Your Headhunter Isn’t Telling You

I was recently contacted by a Global Chief People Officer, who was utterly perplexed. He had been in touch with a dozen top executive search consultants, but none of them had introduced him to any new roles. And he had an immaculate background for a global executive.

Being in his mid-50s, he had started to fear that he was experiencing age discrimination, since nothing else seemed to make sense. And it was at this point that he had come to me as a referral from a mutual friend, another Global Head of Human Resources with whom I had previously worked. She had recommended me as someone who would give him the unvarnished truth, and we had a great dialogue about some personal factors relating to his situation. Out of this conversation came two general factors that I wanted to share, in case it helps others in a similar situation.

If a Company is Looking for Someone as Senior as You… Something has Probably Gone Wrong.

In the past, if not quite the norm, it was still relatively common for companies to reach out to the external market to hire even their most senior executives. But since the 2000s, we have seen the market for top corporate hires gradually decline. Largely due to the proliferation of talent management practices at the corporate headquarter level, most top roles are now backed up by a comprehensive internal Succession Plan. Long gone are the days where companies would scramble to hire positions at high levels from the outside; nowadays, there are a handful of internal hopefuls vying for these roles. And in the case of multinational companies, these hopefuls could be sitting anywhere around the world, ready to relocate to the corporate headquarters when the call arrives.

So if there is a senior leadership role on the market (in this case, a Global Chief People Officer role), there’s a high chance that something fairly unexpected has happened. Perhaps there was a recent exodus of talent, clearing the bench of all potential successors. Perhaps there was a sudden industry shift, leading to a requirement for new skills that hadn’t previously been nurtured. Or there might be a cocktail of personal and performance-related issues behind a decision to bring in new senior leadership talent.

To the individual job-seeker in their 50s, the experience of not being approached for these roles might feel like age discrimination, particularly if they didn’t encounter the same situation when seeking jobs in the past. And who knows, in the case of some individual decision-makers, that’s exactly what it is. But in my experience, the reason they’re not being approached is largely due to the relative scarcity of senior roles at their level. And even when such a role does exist, company decision-makers are under pressure to hire someone with specific attributes to fix an esoteric problem. No compromises.

The ‘Cooling Effect’ of the Corporate Matrix.

The scarcity of the top job in his specific field doesn’t itself explain why this Chief People Officer wasn’t being considered by executive search professionals. Alongside the rise in corporate succession planning, the last decade has also seen a shift in corporate culture away from single-minded ‘top-down’ decision-making, and towards the gathering of a diversity of viewpoints. The process of hiring top senior talent has not been immune to this shift. In the past, it was quite common for executive search professionals to work with a very small number of decision-makers when hiring even the most senior roles. These days there are many more stakeholders, both top-down and at peer-group level, who are brought in to have a say about who should be hired above a certain grade. And the reasons for this are logical. The new senior executive can develop a three-dimensional view of the situation they’re getting into, and the people they would need to work with. And the corporate stakeholders can themselves bear an element of personal responsibility for ensuring the success of their new senior colleague.

The downside to this consensus culture is that the ultimate decision-maker can be reluctant to put forward anyone whom they predict will not be accepted by the majority of these colleagues. This effect is further magnified if the decision-maker is using an executive recruiter, since they can be even more demanding with their requirements. If an executive search consultant veers away from their brief, the decision-maker can be justified in saying: “I came to you as the expert headhunter in your field, so I expect your suggestions to be more accurate. Why are you introducing a person who won’t be accepted by our stakeholders, when I could have found someone like this myself on LinkedIn”?

While it’s never the intention of the headhunter or the corporate decision-maker to box themselves in, there is an element of self-censorship when it comes to putting forward profiles where the senior job-seeker doesn’t have ‘10/10 boxes ticked’ from the outset. It’s not that they are bad people, or narrow-minded and discriminatory people; they’re time-poor, task-focused, and pragmatic in the execution of the role they’ve been allocated. And why is this particularly relevant to job-seekers in their 50s? It’s not necessarily that their age is a decisively negative factor. It’s because they are the ones eligible for the top positions. And with the hiring of top roles comes an increased level of scrutiny, a stricter application of this trend, and hence a disproportionately strong effect.

So What Should You Do?

There is no magic wand that can reverse these two general trends. But I would end this article with a few simple words of advice.

Most importantly, keep positive. You don’t need to feel like you’re constantly on the back foot; you don’t need to apologise for yourself; and you don’t need to waste energy blaming others. It can be emotionally bruising to encounter repetitive rejections, especially on the back of a long and fruitful career. Don’t let this happen. The truth is that some decision-makers do have an age bias. And they’re missing out on some great people. But ‘tune out’ those companies that aren’t able to give you a chance, and focus your efforts on those that can.

As an adjunct to this, be humble. You are not automatically entitled to a new job, the world doesn’t owe you anything. Think of being 75% self-assured, and 25% humble… any more humble, and you’re under-selling yourself. Those numbers mean absolutely nothing, but they’re a good check on yourself if you’re having a bad day and feel like you’re wobbling around the 50/50% mark.

Leverage your existing relationships to the max. Keep in touch with close colleagues and clients from the past, those people who can simply vouch for the work that you do. Personal recommendations from these people are the best way to convince corporate decision-makers to set aside any perceived ‘imperfections’ in your background, and focus on what you can bring to the organisation.

Be active in applying for roles directly and through job sites like LinkedIn. But maintain your relationships with executive search consultants. They still might have that illusive ‘10/10’ role for you. Find the right balance between being responsive without becoming annoyingly over-responsive. If you feel that you’ve been unfairly overlooked over a role, engage with them to explain what they may have failed to notice. And decide for yourself if you can trust their explanation behind what you’re missing from the full list of criteria.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

The Magnificent Power of “I Don’t Know”

Where Knowing Everything Means Knowing Nothing

In my early days as a consultant, it was always tempting to come up with an answer to any question a client would ask me. The classic Fake-It-‘Til-You-Make-It Strategy. Or there was the Deflection Strategy, where you can politely dodge a question with phrases such as “I’m not sure I’m the best person to answer that…” or “Here’s what I can tell you…”. I’ve seen plenty of other panicky nonsense too. The Give-An-Answer-To-An-Entirely-Different-Question Strategy works surprisingly well, especially if the client isn’t really listening properly in the first place. And then there’s the Buy-Time-With-A-Long-Winded-Answer-So-That-Everyone-Forgets-The-Original-Question Strategy. Sorry, where were we?

I am grateful to have been surrounded by mentors who demonstrated how to avoid these traps. And these days, I really enjoy saying ‘I don’t know’. When you confess to not knowing the answer to one question, it accentuates the credibility of all your other answers. So while there’s certainly a skill in being able to concoct intelligent answers to every single question, be careful not to bury your bright diamonds of knowledge under a thick layer of coal.

Maybe This Time I Should Shut Up and Listen

You’re a thoughtful, worldly, professional human being, and you have every right to express your opinion on any topic you choose. But there are times when saying “I don’t know” is a matter of deference to others who have more depth of personal knowledge or experience. There’s something powerful about admitting that you still need to learn from others on a particular topic rather than professing to know all the answers yourself.

Personally, I have loved sharing details from the fifteen years I have lived and worked in Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and Mainland China. But when I’m asked questions such as “What do they think of this in Japan?” or “What do they do about that in China?”, I’m very wary to give an answer unless I’m sure that I can make an accurate generalisation. In this regard, saying ‘I don’t know’ can be a sign of humility, rather than a sign of ignorance. I wish that more news commentators would at least preface their opinions with similar disclaimers. Or indeed more privileged white males when asked their opinion of the #MeToo movement…

Authenticity, Vulnerability and Curiosity

In business as in personal life, we need to be our authentic selves. It’s just too tiring trying to be anyone else. So if you’re in a situation where you don’t know, admitting so can be a great way of breaking down walls and building trust. There’s a time for confidence and assertiveness, and then there’s a time for refreshing honesty.

The world is bewilderingly complex, and we shouldn’t be too hard on ourselves if we can’t speak intelligently on the geopolitics of Syria, the effects of climate change, and the workings of Blockchain for a combined ten minutes. But there’s a difference between perpetual curiosity and willful ignorance. We need to be continual learners and embrace each ‘I don’t know’ not as a badge of pride, but as a prelude to discovering more.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

Should We Stop Using the Word ‘Expat’?

I’m always wary when someone is referred to as an expat. It’s a term still commonly used by Human Resources professionals to refer to employees who have been sent on assignment overseas. But maybe it’s time to stop using this word altogether.

The Ickiness

My biggest complaint is the neo-colonial aspect to the word itself. It has been great to see how employees from every corner of the world have now been expatriated from their home countries. Let’s send more qualified Kenyans to Kuwait; Vietnamese to Venezuela. But to me there’s still a congenital ‘whiteness’ about the word. Why am I an expat, but a builder from Bangladesh is a migrant worker? Aren’t we both just different kinds of economic migrant?

The Detachment

Referring to an international assignee as an expat can create a barrier between themselves and the people around them. The title becomes an excuse for them to disassociate themselves with their office surroundings, and not truly engage with their host environment. It lets them group themselves with other ‘expats’, define themselves by their differentness, and engender an us-versus-them mentality. Before long, when an ‘expat’ has a bad day they might say ‘I hate this country’, rather than say… ‘I’m having a bad day’.

The Ego

The term brings with it a sense of elitism and entitlement. A company should certainly help an international assignee with their lives, be it getting through the pain of relocation, helping with schooling costs, or advising on tax issues. But referring to the assignee as an expat adds an extra layer of status, which once given can be hard to retract. The next generation of internationally-mobile employees should be taught that an assignment is just part of their job description, not a perk, nor a badge of honour.

I was inspired to write this article in part because I hear a loud drumbeat of nativism around the world, especially tied in with anti-immigration sentiments. I’m personally the son of political refugees, and have been an economic migrant in Asia for over a decade. I also believe that a migrant should do their best to assimilate into the fabric of their new society. But it never escapes my attention that we have double standards for migrants in the West versus Western migrants living in the East. To some extent, global multinationals and HR leaders can help to reconcile this double standard by limiting the use of this term.

What are your thoughts? If you agree, what terminology would you suggest we use? Do you disagree, and am I just yet another hapless victim of political correctness? Do you have any stories of ‘Expats behaving badly’? Your answers and comments gratefully received!

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

Sweat, Balance, and Momentum

I passed this man on the streets of Shanghai and was immediately inspired.

Sweat

You can be the most gifted in your field, but without Diligence you won't succeed. Don't be complacent of your superior skills: Lean into your work, and commit.

Balance

Sweat is useless without Sustainability. We all need to balance our work, leisure and family priorities to last the full course. Maximise your capabilities, but be kind to yourself and don't... overload your rickshaw.

Momentum

Sustainable effort needs to be funneled into the right Direction. We all have days where we work hard, and yet still question whether anything tangible was achieved. Have the curiosity to seek out and define your goals, and the daily persistence to achieve them.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the Instagram version, see here.

Lazy People: The Unsung Heroes of the Corporate World?

By including lazy people in a diversified decision-making team, you can arguably focus more on achievable goals with more predictable results.

Lazy people: We all know at least one of them. And we prefer to weed them out as soon as possible from the corporate environment. They stand out as low performers and make troublesome examples of themselves in the team.

But are we sometimes dismissing these people prematurely? We tend to view lazy people at one end of a spectrum, with highly productive people at the other. But what about their similarities?

Lazy people and productive people both want to get their jobs done as efficiently as possible.

For productive people, motivation lies in getting on with other things. Lazy people are motivated to get on with precisely nothing. But isn’t this a shared motivation that we should be harnessing from both angles? Especially since the motivation for lazy people to do as little as possible is arguably stronger than the motivation for productive people to do more.

The scenario I have in mind is where a decision is made by a group of engaged, productive executives, only to find that the implementation of the idea fails dismally due to lacklustre uptake or poor compliance to a process. If you have a lazy person with a seat at the decision-making table, you are much more likely to eschew idealism and avoid these unpleasant outcomes.

A lazy person will take into account the ‘lowest common denominator’ of how people actually work, rather than how we wish they’d work.

A lazy person is more likely to find time-saving loopholes, based on the simplest and most practical solutions.

A lazy person will help to set the right expectations about what percentage of any high-minded plan will be successfully completed in reality.

The Lazy Person in All of Us

Naturally, it’s dangerous to promote people with these qualities, since it sets a risky precedent for the company’s culture. And they won’t be the people who come up with many original ideas themselves. But by including the voice of a lazy person in a diversified decision-making team, you are arguably more likely to focus on the most achievable goals and get more predictable results.

Having held your attention for this long, I should admit that it’s, of course, a fallacy to think of anyone as ‘lazy’. We all exhibit the qualities of the ‘idealistic’ person in matters that make us passionate, and the ‘lazy’ person in matters that don’t.

So the next time you’re deciding on issues of this nature, it’s useful to look around at your team, and work out which person could play the part of the ‘lazy person’. And if you can’t work out which one to choose… then it’s probably you.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the Boss Magazine version, see here.